Mr Fables has turned a corner into a new year that holds some significance (if you tally these sort of things up). A milestone birthday with a reading challenge1 to match.

After taking on …

57 Books for my 57th Year then a more modest 23 Books for 2023 there were 24 Books for 2024 …

… it feels natural to match this year’s challenge to the ‘25’ of 2025. But there’s a twist; the challenge is to source twenty five books originally published in 1965. Those of you who are as adept with numbers as you are with words will be able to ‘guess the milestone’ associated with my personal ‘publication date’.

The List

At Bertram’s Hotel (Agatha Christie) - A delightful mystery seen through the eyes of the ever-alert Miss Marple. A hotel serving a slice of ‘the way things were’ with buttered muffins for afternoon tea, a cast of retired generals and forgetful clergy, and the unassuming persistence of Chief Inspector Davy. An heiress, a feckless racing driver and a young ward - what connects them?

An American Dream (Norman Mailer) - Every time I sat down to write this review, the word visceral has careened into my thoughts. This is a downward spiral into violence and deception, a piercing insight to the dark underbelly of a world of privilege. It is who you know and the stories you tell about yourself that shield you. However low the characters sink - and they plumb the depths - their place in society governs the outcomes. An American dream where all men are not created equally. Raw, vivid and brutal, this is a sleazy tale, told with a relish that speaks volumes for the appetites of the society it explores.

A Suspension of Mercy (Patricia Highsmith) - Brilliantly conceived and written, this is imaginative work. An author given to flights of fancy tries to imagine life as a murderer - a character in the books and screenplays he writes, perhaps - sketching out notes and details that begin to raise suspicions when his wife disappears. Tension is maintained throughout, credible characters deepening the mystery at every turn of the page. A sort of whodidnotdoit.

The Tin Men (Michael Frayn) - This is an absurd satire on British business, the Establishment, science, and society. Writing that would not be out of place in a Monty Python sketch and a cast of caricatures that plays perfectly into the bizarre plotlines. Running gags keep the pot boiling - a ‘novelist’ who is writing his book on the company’s time, starting with the reviews; an ex-military spy who sees plot and subterfuge at every turn; a Chairman whose idea of leadership is silence, peppered with the occasional thoughtful ‘hmmm’. Easy-to-read, occasionally funny … very much ‘of its time’.

Dune (Frank Herbert) - The scale of this epic novel could be overwhelming. The worlds imagined into being by Frank Herbert bestride galaxies. But the story narrows down into a tale of one boy’s destiny. The ‘hero’ (Paul Atreides) is a Duke in exile after the violent overthrow of his father. Religious and political manoeuvrings dominate the narrative. It helped that I had seen the first of two ‘Dune’ movies, so the central premise and the characters at the heart of it were easy to place. The quasi-religious narrative is the hardest to fathom, but each chapter begins with ‘quotes’ from a history of the time; this is such a smart writing device. Readers are divided about Herbert’s prose, and if at times there were unusual constructions or phrasings, for me it deepened a connection to a new and unfamiliar world. This epic is broken into 3 ‘books’; the first two are immersive, drawing you in through the slower pace of the narrative. The denouement, for me, was a little rushed, perhaps a little ‘convenient’. That said, so many of the ideas - global greed, resource stripping, climate hostile living, water-saving ideas etc - feel contemporary.

The Looking Glass War (John Le Carré) - in the post-Second World War era, those mired in the business of national security were wrapped in a new order, their behaviours shaped by memories of old enemies and ‘how it was’. This is the story of a Department searching for purpose; characters hewn from ‘back then’ clutching at tempting opportunities to do their bit. (Deliberately?) ponderous, this is a spy ‘thriller’ that lacks urgency, pace or global scope. Its narrowness wraps a claustrophobic blanket around the team formed to mount the operation. Politics and patriotism stir the pot, but humans, with all their flaws, will deliver success or failure. Bleak stuff.

(17 February 2025) I will be taking a short break from books published in 1965 to focus on my writing.I have ‘The Way of the Fearless Writer’ by and to dip in and out of.The Man with the Golden Gun (Ian Fleming) - my memories of Fleming’s James Bond are shaped by the movies, my early teenage self impressed by his diffident air, devil-may-care attitudes and the scantily-clad beauties who sprawled across his hotel beds. The books and Bond’s attitudes - check out ‘Thrilling Cities’ to sense for yourself how closely they reflect Fleming’s own ‘days of empire’ mindset - haven’t aged well, and in this case the plot is a long way removed from that which showcased Christopher Lee’s suave Scaramanga, The Man With The Golden Gun in the movie. The book is short, easy to fly through, but lightweight and ‘of its time’. Not one for a re-read.

God Bless You, Mr Rosewater (Kurt Vonnegut) - The star of this particular show is an obscene amount of money, the value of a Foundation administered by members of the Rosewater family (from the age of 21 until death, unless they proved to be insane). The plot revolves around people’s relationship to the vast sum; indifference, greed, and conflict all rear their heads as the protagonists either try to dispose of it through charitable endeavours or grab a slice of it by legal shenanigans. It seems clear that the author is having a sharp nip at the heels of US society and its obsession with wealth … black humour abounds and Eliot Rosewater is the fall guy because his approach grates against the aspirations of ‘the American Dream’. That he wins out in the end is a triumph, not just for the character, but also for those who would put others before themselves.

A short break from 1965

There Are Rivers In The Sky (Elif Shafak) - oh, my. I may well have a new ‘favourite’ novel. Perhaps, equal first. This is such exquisite writing and incredible storytelling. The tale cuts back and forth between the lives of three central characters, connected for the reader by the remarkable history and oral tradition of Mesopotamia. Every character is richly drawn, every detail plausible and researched, you feel. Slowly the threads tighten and you feel that each character’s journey is drawing them all closer together. The darkness of the closing chapters is lifted by the hope in the final moments, the beautiful ending the story deserves. As a writer, I am in awe of the phrasing, the way words are woven together … the narrative style keeps you present every step of the way. I absolutely love this book; I know I shall reread it again and again.

Strangers on a Train (Patricia Highsmith) - quite probably the most tense, wrought, utterly absorbing thriller I’ve read in recent years. The tension is so expertly ramped up, almost inducing the same levels of guilt in the reader as the protagonist who is unwillingly dragged into the machinations of the stranger who wants to use him as the weapon in his murderous plans. A brilliantly written debut novel that kept me on edge from start to finish.

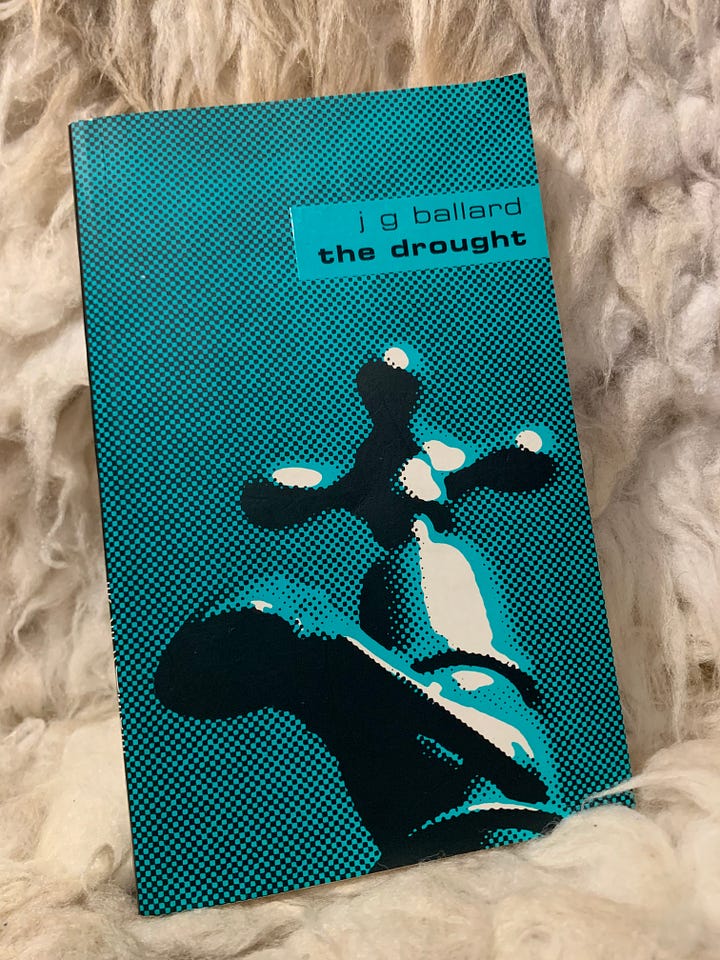

The Drought (JC Ballard) - Like Frank Herbert’s Dune, The Drought feels anything but 60 years old. The themes of individual and collective responses to an environmental catastrophe feel like a contemporary warning, a prescient imagining of a future that may yet unfold. Exceptional circumstances breed unlikely alliances and extremes of behaviour but also incredible ingenuity. The imagined world feels plausible and the characters representative. JG Ballard writes both densely and sweepingly, his words painting pictures, almost like a screenplay. Imaginative, chilling; a future we don’t want to imagine into being.

Not 1965(April) Slow Horses (Mick Herron) - Does it change the way you read if you have seen the plot unfold over 6 episodes of a streamed ‘Season’? Does it improve the book or diminish it if you no longer have to imagine the characters into being because the casting agent and the actors they chose have already done that? This is a dilemma. But, when the plot is this good, when the writing is so excellent, and when the cast is so strongly sketched out, it feels like it matters little. This is a taut thriller, brimful of outstanding (the writer in me says enviable) dialogue. Thoroughly enjoyable. I shall gather up more books from the Slough House series and read them with even greater distance from my viewing of the television drama, all the better to let my imagination run wild with the author’s spellbinding imaginings.

The Fortunate Pilgrim (Mario Puzo) - This is the richly-told, colourful tale of an Italian immigrant family doing what it takes to survive in the poorest tenements of New York in the Depression. It is the details that grab you, and the unfolding tension between the traditions, the expected behaviours of the homeland, set against the brash, loud, money-focused ambitions of this new world. Lucia Santa, the matriarch must somehow steer her family through the hardships that world creates. Excellent writing from the author who would go on to win an Academy Award for the screenplay of his acclaimed novel ‘The Godfather’.

The Dark (John McGahern) - Dark, indeed. A traumatic childhood in Ireland, an abusive father and all the uncertainties of education and future employment for a youngster with no advantages. An absorbing tale of a young man who battles the context while wrestling with his inner doubts. Brilliantly written, lyrical almost - poetic prose, perhaps - with a fascinating ‘point of view’ at the heart of the storytelling. Deep, dark, but hopeful too.

Moominpapa at Sea (Tove Jansson)

The Magus (John Fowles)

The Black Cauldron (Lloyd Alexander)

The Mandelbaum Gate (Muriel Spark)

The Town in Bloom (Dodie Smith)

The Mind Readers (Margery Allingham)

Further non-1965 distractions

(May) The Bourne Identity (Robert Ludlum) - Like Slow Horses, there is a risk that familiarity with the film franchise might compromise the read but unlike Mick Herron’s like-for-like ‘scripting’ of the TV series, this opening salvo in the Bourne story offers a density and a plot line that differs enough from the movies to captivate and lose the reader in the depths of the central protagonist’s amnesia. Both reader and central character wrestle with the complexity and the twists and turns that an evolving understanding provokes. Matt Damon may loom large in our imagination but that is a helpful fixed point in a fast-moving story that races through Europe and finally to New York where ‘it’ all started. Compelling, imaginative.

(June) The New York Trilogy (Paul Auster) - The first story in this renowned collection City of Glass is so cleverly written. The premise of the plot is cleverly conceived and brilliantly executed, with a reclusive central character emerging to weave a complex tale of imaginative hooks and connections. A writer at the peak of his powers writing about a writer whose own have faded, a man who has placed himself on the fringes brought back into the heart of a story that echoes with truths and lies.

(June) Conclave (Robert Harris) - A papal election is a rare occurance; there were only eight in the 20th century. When Robert Harris wrote this thriller about an imagined conclave, the gathering of cardinals to elect a new pope from among their number, Pope Francis was only three years into his 12-year papacy. It is remarkable, therefore, in light of their rarity and secrecy of these gatherings, that Harris has fashioned a novel about them with such a sharp ring of truth to it. The details draw the reader in; even the most secular of souls would be hard-pressed not to be impressed by the centuries of tradition writ large, while at the same time, the stench of ambition and corruption smell all too contemporary. This is a real page-turner, the outcome of which is in doubt until the final pages.

Non-fiction, not 1965

The Notebook - A History of Thinking on Paper (Roland Allen)

Yet to be sourced

Modesty Blaise (Peter O’Donnell)

Stoner (John Williams)

Going to Meet the Man (James Baldwin)

The Orchard Keeper (Cormac McCarthy)

Closely Watched Trains (Bohumil Hrabal)

Full Tilt (Dervla Murphy)

Black Rain (Masuji Ibuse)

The Sense of Wonder (Rachel Carson)

Hotel (Arthur Hailey)

The Vintage Bradbury (Ray Bradbury)

The Painted Bird (Jerzy Kosiński)

La Chamade (Francoise Sagan)

Ariel (Sylvia Plath)

The Hot Gates (William Golding)

Fox in Socks (Dr Seuss)

Asterix and Cleopatra (René Goscinny and Albert Uderzo)

The River Between (Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o)

Full credit to our friend Mike Hughes for the idea though

is claiming part authorship. I am claiming full credit for putting the idea into practice.

What a great project! Awesome to see the list you've got going here.

This is such a great idea! And I will keep this list in mind, because some titles sound up my alley. Maybe I will do 26 for 2026 with books published in 1995. You certainly made me want to. But yeah, sourcing sounds hard.